Shortly before the second invasion of the Greek cities, the Persian General Mardonius looked out at the approaching Greek coast line and said1,

“These Greeks are accustomed to wage their wars among each other in the most senseless way… they seek out the fairest and most level ground, and then go down there to do battle on it.

Even the winners leave with extreme losses; I need not mention the conquered, since they are annihilated. Clearly they should settle differences by any means rather than battle.”

The “senseless” Greek fighting style could be summarized as such:

Decide war with a single battle. Decide battle with a single clash.

Like in the movie The Purge, Greek culture believed the ideal way to resolve conflict was to condense all the violence into the single moment.

So while every other Iron Age military was developing weapons tech to increase efficiency (viz: more kills, less casualties), the Archaic Greeks (c800+BC) mostly abandoned the archers, cavalry, and siegecraft of Bronze Age in favor of one unit type: the hoplite in phalanx formation.

While every other military was developing battles tactics, the Archaic Greeks abandoned all attempts at tactical advantages for one and only one “battle plan”: Hit the enemy head on with as much force as possible.

Greek warfighting seemed senseless to the rest of the world because it was needlessly inefficient.

Hoplite-style fighting required a huge amount of mechanical energy relative to killing power. It also risked many more lives than a combined-arms approach. It ALSO required a level of physical and mental fortitude far beyond that of the typical Iron Age soldier.

But because of this, the Greeks developed a different kind of men…

It’s not surprising that Greek culture is the only ancient culture to not only prize masculine ethics but also male aesthetics.

If you grew up in an Archaic Greek city, the following beliefs would be so deeply embedded into you they would seem obvious:

Only a coward would try to kill without risking death himself.

The best kind physique was the one that allowed you to wear 70+ lbs of armor and weapons, and push against an equally armed wall of spears for 40-60 minutes. (Think HIIT to the death.)

War wasn’t about proving who had the better city-state. It was about proving who had the better men.

These beliefs formed a “ruleset” that guided not only their behavior, but how they evaluated life.

In other words, the Greeks played a different game…

In Hardcore History, Dan Carlin has pointed to how something about a culture allows warriors fight a certain way.

The Romans tried to emulate the Greek phalanx, but they couldn’t pull it off. But then they created the uniquely Roman legionary and proceeded to take over the world.

Chinese emperors tried to recreate the samurai by importing weapons and instructors from Japan. But they could not create a Chinese samurai.

Something about growing up in Japanese culture allows a man to fight like a samurai.

Something about Greek culture allows a man to be a hoplite.

Something about Roman culture allows a man to be a legionary, Medieval European culture to be a knight, steppe culture to be a horse archer, and even modern American culture to be a US Marine.

The something is the game.

Society is a game. Culture is the point system.

In game theory, a game is any situation where your actions and the actions of another determine your outcome.

A game is defined by its rules:

The conditions for victory (and defeat).

What you’re allowed to do in order to achieve victory.

How progress is evaluated (scored).

Society is a particularly complex game (containing many interlocking mini-games). The points might not be explicit (except in China), but we do have rules.

Laws are our explicit rules. If you break them you will get penalized. But most of the time, explicit rules don’t affect our day to day.

Explicit rules themselves are meant to reflect implicit rules (customs, norms, and morals). Implicit rules are the ones that actually matter.

For example, jaywalking is technically illegal in both New York City and Singapore. But you will never get a ticket for it in NYC. In fact, you will get penalized (yelled at) if you don’t jaywalk when the rest of the crowd is crossing. In Singapore, not only will you get a ticket, you may cause shock and outrage in both authorities and general passersby.

The modern culture wars are essentially being fought over which ruleset ought to determine the game of Western society.

Society is a game that offers certain expected outcomes based on behavior. Culture incentivizes certain behaviors through implicit rewards and punishments. This ‘cultural point system’ affects the ways we instinctively act— Especially the way men fight.

Culture makes Game (Perceived Payoffs).

During his campaign into Persia, Alexander the Great was gravely insulted when one of his non-Greek allies suggest he lead a surprise night attack. To Alexander the mere suggestion of an unfair fight was an insult to his manhood. He said,

“The policy you are suggesting is of bandits and thieves, the only purpose of which is deception. I cannot allow my glory always to be diminished by Darius’ absence, or by narrow terrain, or by tricks of night. I am resolved to attack openly and by daylight. I choose to regret my good fortune rather than be ashamed of my victory”2

To Alexander, raised in Greek-inspired culture, the “game” was about achieving glory not just defeating opponents. To win by deceit wouldn’t actually “count” as a win.

Society’s need defined cultures to ensure that their members are playing the same game. As discussed in Episode II: Chiefs to Kings, a common morality (implicit ruleset) allows a large group to operate in unison. If we all feel the same way about a given event, then we can count on each other to take complementary actions.

So cultures reinforce their given values so that they become “obvious” to its members.

For example, Western culture preserves the assumed value3 that “one should fight against the odds”.

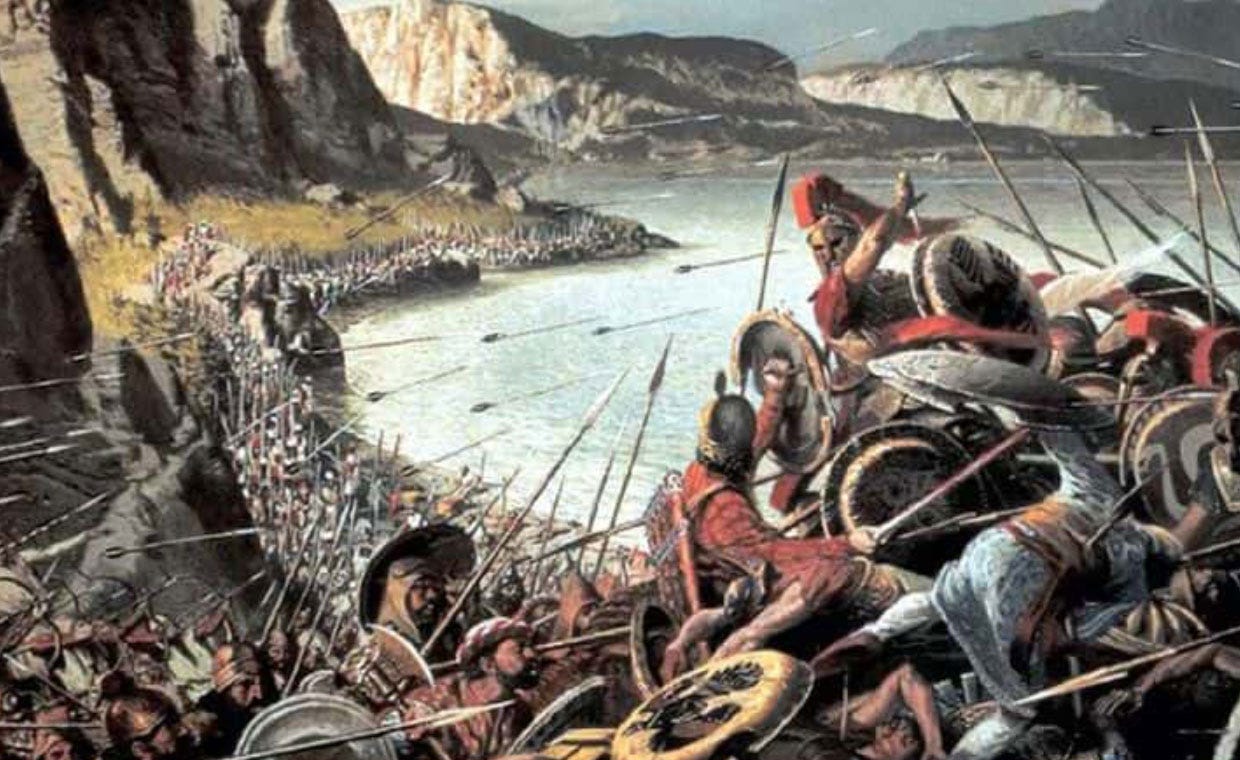

We immortalize the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae specifically for how they lost.

We cheer for Rocky just for going the distance the Apollo Creed the first time around. (Which to anyone with taste was much more entertaining than the fairy tale ending of Rocky II).

We remember the Alamo.

While there may be a biological element to valuing selfless heroism (viz: Episode 0: The Winner Effect), this value has at least in part been inherited from previous cultures like the Archaic Greeks.

Cultural values feel objectively true and obvious because they affect our feelings before our conscious mind registers.

Had Western culture descended from a different warrior people such as the Mongols4, it’s less likely this ethic would have become part of our values.

Culture defines ‘Game'— the perceived payoffs of certain actions, specifically the conditions of victory.

Fighting for ‘glory’ is a different game than fighting for ‘survival’— even if the actions look similar most of the time.

Fight for ‘rights’ is a different game than fighting for collective validation.

These perceived payoffs determine the strategies one would choose on how to act.

Culture makes Strategy.

Every martial art has the same ultimate goal: To defeat your opponent in a fight.

But there are many ways to “defeat” someone.

Each martial art developed as a strategy to win the game of fighting. Presumably, it was adopted because it was rewarding under initial conditions.

Muay Thai centers around the powerful round kick because it was initially used in battlefield combat as an alternative to swing a short sword.

Wing Chun focuses on close quarters traps and strikes because it was (according to legend) created by a small woman who was trying to prevent a much bigger man from forcing her into marriage.

Culture determines how people define ‘victory’. This defined goal then leads to different strategies for how to accomplish it.

Like moral perceptions, each strategy represents a model of reality.

Each martial art is a strategy on how to win the “game” of fighting. It relies on a certain model of what fighting “really is”.

Similarly, every social ideology represent a strategy on how to win the “game” of fulfillment (and happiness, well-being, survival, etc.). Like martial arts it relies on a certain model of reality.

The model of reality further determines the techniques one chooses to execute a certain strategy.

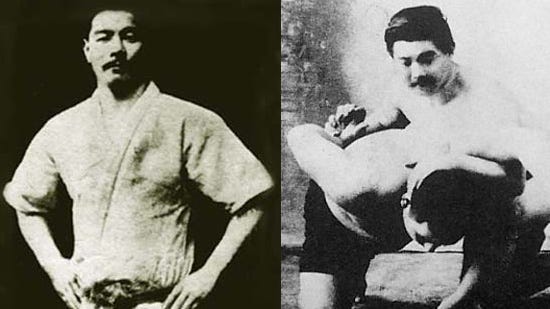

This apparent in the evolutionary split between Judo and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

Culture makes Technique.

In the 1880’s, long time Jiu-Jitsu practitioner Kano Jigoro decided training in kata (forms) was not a good model for creating effective fighters. He was creating a new training style based in randori (free sparring). He found that while pins and submissions signified dominating randori, breaking your opponent’s posture was the easiest technique to accomplish that.

He sent his top students around the world to demonstrate this new take on an old art. One of his students, Maeda Mitsuyo, took the art to Brazil where he taught the now famous Gracie family.

In Japan, practitioners followed Kano’s primary method of breaking postures. This developed a greater emphasis on full control throws. It eventually became modern Judo.

When adapted for sport, their explicit point system reflected Kano’s strategy. Pins and submissions could win, but they were secondary in value to the high-arcing throw (ippon) that has become the cornerstone of Judo. These were codified as the Kodokan Rules of Judo.

But in Brazil they didn’t accept the new rules.

That’s because they didn’t accurately reflect the Brazilian style of fighting.

Unencumbered by a history of Bushido, and fueled by its own Brazilian culture, the Gracie family focused on the ground submission aspect of the art. They developed a subset of techniques that was always possible in Judo, but for some reason the Japanese never thought of.

According to John Danaher, BJJ philosophy can be summarized in a four steps:

Bring your opponent to the ground. (So he can’t punch you.)

Get past his legs. (So he can’t defend himself.)

Gain and maintain a dominant position. (So you can punch him.)

Submit him.

The strategy is not that different than that of judo. But they have a very different technical focus which may have been inspired by other Brazilian movement patterns such as capoeira, samba, and cultural elements.

Their implicit values were also reflected in the BJJ sport point system.

BJJ doesn’t reward the quality of a takedown (unlike the ippon in Judo which wins the match.) Many BJJ players skip takedowns altogether and pull guard instead.

Since the guard is an integral part of the style, their point system rewards passing it. (No one pulls guard in judo—it would actually count as pinning yourself.)

So even though a BJJ practitioner and judoka have the same strategic roots, they tend to focus on different styles.

And more significantly, even when they do the same techniques, they evaluate them differently— the same events have different meanings.

Modern society continuously shows how the Left and the Right make totally different meanings of the same events— and therefore prescribe different actions. It’s not because the other side is lacking in brain cells (though many use that as a lazy explanation); It’s that cultures tend to revert to previous patterns evaluation when trying to achieve a new goal.

Differences in evaluation ultimately leads to how a person does something… even with something as simple as a left hook.

Culture makes Style.

All boxers value speed, power, distance management, and efficiency. But not all value these values to the same degrees.

American/Latin American boxers typically throw the left hook in a way that maximizes power and speed at the expense of range and efficiency— High shoulder, elbow locked, 60-90 degree hip rotation, fist often vertical. (Think Tyson, Roy Jones Jr., Canelo Alvarez.)

Eastern European boxers throw the left hook in a way that maximize range and efficiency at the expense of speed— low shoulder, 15-45 degree hip rotation into chest and arm action, fist always horizontal. (Think Klitschkos, Gennady Golovkin.)

It’s not that Americans don’t care about range or Russians don’t care about speed, it’s that with a punch like a left hook, a tradeoff has to be made.

The American-style of boxing likely came from American subcultures that particularly value hip agility. Compare the jazz and swing dances of the 1940’s to the movement patterns of Sugar Ray Robinson. Can you imagine Wladimir Klitschko doing the Lindy Hop? I can’t.

I once asked a Russian sparring partner why he and the other Eastern Europeans in the gym “punched long”. He said it’s because historically Russians needed to fight on ice. If you rotate your hips “American style”, you’ll slip.

I don’t know if that’s true, but it could be. The Russian loose hook may also have roots in the casting punch (a punch that is whipped from the core). It’s popular in sambo because if you miss you get up in the clinch— This may also be useful when fighting on ice.

Both styles can be used effectively5. They are just alternate tradeoffs initiated by culture.

Which style is “better” depends largely on context. Hence styles make fights.

Ronda Rousey seemed invincible until she met an aggressive striker who could avoid the clinch.

Similarly the Greek hoplites put up an insane killing ratio6 against the Persians in both wars, but the same style led to them getting merc’ed by the Romans who played a totally different game.

Many cultural disputes are not actually over competing values as much as competing tradeoffs.

For example, all Americans value both Freedom and Safety. But pandemic mandates revealed which value a person valued more.

Some were unwilling to give up a huge amount of freedom for what seemed like a small increase in safety. Others cared so much about safety that the tradeoff was worth it. Other still were so concerned about safety, that they gave up traded off the value of rational discernment to pledge allegiance to the ideology that they hoped would protect them. (Viz: On Perimeters and Pyramids.)

But most importantly, the stylistic tradeoffs one makes eventually leads to how one perceives everything else.

Culture dictates reality.

The Greeks fought a “senseless” way because of their peculiar values. And they also had peculiar values because of their “senseless” way.

Imagine being the first Archaic7 hoplite to suggest you send some light armed troops for a flank attack… You would be probably shamed to such a degree that any possible benefit to that wouldn’t be worth it— or more likely, the thought would never cross your mind.

Once culture forms to create a certain model of reality, the model eventually becomes all they see. In other words, the map takes the place of the territory.

Therefore traditional Japanese judoka wouldn’t think of a berimbolo roll, a Mexican boxer wouldn’t think to throw a casting punch, and men other than the ancient Greeks wouldn’t think “Hey, why don’t we bulk up?”

Modern MMA has taken martial arts outside of theoretical models and back into something close to “reality”. But the same errors of abstraction are occurring in other areas of society.

Social ideologies are the equivalent of early martial arts— They are strategies based on a model that was accurate at some point, somewhere.

Moral values are the equivalent of point systems— They are evaluations based on executing a strategy within a given model.

But just like you can perfectly execute a five point throw in a street fight, then proceed to get stomped in the face, you can “score well” according to a certain ideology and still be totally miserable.

Society is a game. It is a web of interaction between many participants and spectators that offers certain results to its participants based on the actions they take.

Culture is the point system. It determines how you feel about situations, how you aspire to be, and even how you would throw a punch.

So it’s important to recognize the rules you’re following as they determines who you are and the nature of your reality.

Also, don’t pull guard in a streetfight.

This article contains some of the stuff I had to cut from the next episode of History of Man coming soon.

Episode III: With Your Shield Or On It covers how the Greco-Persian Wars, Peloponnesian Wars, and Alexander’s campaign into Persia represents different phases of a culture war that had determined how men are perceived today.

If you’re not already, make sure to subscribe. I’ll be posting articles more regularly from the stuff I can’t fit in the podcast episodes. Keeping everything free. Any kind of support is appreciated.

*According to Herodotus, who wasn’t there and was only 9 years old at the time.

The Western War of War, Victor Davis Hanson

Assumed values are different than “values” in that they are not consciously perceived nor chosen. Instead, assumed values are the perceptions that we measure our chosen values against.

Steppe peoples developed a different take on honor due to different payoffs on the open plains. On horseback, if you were losing you could actually get away. Whereas on foot, if your side was losing you were sure to die anyway, so you might as well go out swinging.

As an American who used to teach kids boxing classes, I have to admit the “Russian style” is more suited to most people. While more pros use the American style, it requires agility and coordination to be used effectively that the average person doesn’t have.

At Thermopylae the Greek allies killed 20,000 to only 4,000 lost. No losing infantry would come close to 5:1 kill ratio until machine guns.

Of course upon exposure to foreign armies like the Persians, Greeks in the Classical era did start adopted combined arms. This adoption of foreign ideas was essentially the cultural element of the Peloponnesian Wars. (Covered in Episode III: With Your Shield or On It.)